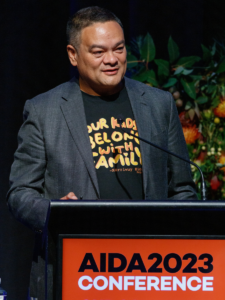

Professor Kelvin Kong, doesn’t just hold the distinction of being Australia’s first Aboriginal surgeon. He carries with him a responsibility to ensure he won’t be the last.

A proud Worimi man, father, son, brother and ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon, Professor Kong has become a powerful voice for equity in health. His journey into medicine began early, shaped by the example of his mother, a nurse who looked after many in their Community.

“My mother was a nurse who looked after a lot of people. Everyone would come to our house for help,” he recalls.

“My sisters and I were always around, helping out with things like suture removals, wound dressings, and cast removals. It was a hub of activity.”

But it wasn’t until high school that he started to see the deeper reasons why his family home became an informal clinic.

“I started realising there was this inequality,” he says.

“Why were they coming to us? Why not the hospital? Why not a doctor?

Purpose-led Practice

These early experiences set the course for a career not just in surgery but in structural change.

Professor Kong completed his medical training at UNSW and became a Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons in 2007. He now practises in Newcastle (Awabakal Country), treating public and private patients across several hospitals.

Reflecting on the significance of being the country’s first Aboriginal surgeon, Professor Kong expresses dual emotions.

“It’s hard to put into words. I’m incredibly proud. But it’s also a reflection of the system,” he says.

“We shouldn’t still be celebrating ‘firsts’. There are so many brilliant people out there who could have, should have been given the opportunity earlier.”

Supporting the Next Generation of Doctors

Professor Kong’s advocacy extends well beyond the operating theatre.

As a former Board Director of the Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association (AIDA), he’s contributed to national efforts to support and grow the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander medical workforce.

“AIDA has been absolutely critical,” he says.

“It’s been a place of support, advocacy, and connection. For me, it’s not just a professional association – it’s a family.”

He adds: “Being on the Board allowed me to contribute in a different way. To help shape strategy, advocate for change, and support the next generation. That collective strength, that’s what keeps us going.”

AIDA’s vision is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have self-determination in a culturally safe health system where doctors are not just present but empowered to lead by drawing on the strengths of their culture.

That vision is slowly becoming a reality. In 1997, there were just 24 known Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors in Australia. By January 2025, that number had grown to 921, including 388 doctors in training. Still, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors make up just 1% of all doctors in training nationally.

Among those trainees, the challenges remain significant. The 2024 Medical Training Survey found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors in training experience racism at more than double the rate of their peers. And are five times more likely to be in be practising in remote and very remote locations.

Recognition and Responsibility

In 2023, Professor Kong was named NAIDOC Person of the Year, a moment he describes as humbling and shared.

“These awards aren’t about individual success,” he says.

“They’re about Community. And when I received it, I felt it was shared with my patients, with my family, with every person who’s supported me on this journey.”

Looking ahead, Professor Kong remains focused on the deeper, systemic challenges that shape Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health outcomes.

“There are structural problems,” he shares. “There is still racism. Still barriers to access.”

“We need to centre Community voices, embed cultural safety, and support more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to enter and lead in this field.”

His vision for change goes beyond treatment.

“We also need to take responsibility, not just to treat, but to listen and to walk alongside.”

For Professor Kong, the work is far from over. But the path he’s creating for others is already being felt.